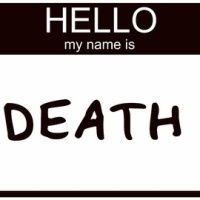

It’s dogfight time. Laurel Leigh’s BABY KILLER is a memoir about a splintered family grappling with questions about a young man’s guilt or innocence. Getting ready to revise the full manuscript, Laurel has asked us to examine the opening—here’s an excerpt. Dogpatch Writers Collective occasionally posts these excerpts of our group critiques of work in progress, and your comments are welcomed.

From Baby Killer

Nursey tells me everything she’s learned: Baby Alex had been beaten before. He visibly showed signs of abuse according to the emergency-room doctors. It’s unclear how Alison was or wasn’t involved in abusing him. On the evening of his death, the baby woke up and threw up and peed on Anthony. Nursey isn’t sure whether the vomit provoked the crucial beating or whether it was an aftermath. Anthony and Alison took the baby to the hospital hours later when they realized something was wrong with him.

“An investigator called me,” Nursey tells me.

“You talked to an investigator?”

“She wanted to know what people, you know in the family, had said about Anthony. I told her, ‘I’ll help you but I don’t know everything.’ So I guess I’m working for the prosecution if anything, nailing the coffin in the head.”

At another time my sister’s off way of describing things would make me smile and want to hug her.

Read a longer excerpt at: http://www.laurelleighwriter.com/publications/baby-killer/

Comments from the Dogpatch:

Laurel,

Opening chapters are tricky. James Joyce — it always seems to come back to Joyce for me, doesn’t it? — said he decided whether or not to buy a book based entirely upon his reading of the first page. Fair or not, this is probably not an unusual sentiment for many readers, though in Joyce’s case money was always tight almost his entire life, so his fiscal discretion was understandable.Ideally, those first few pages of any good book are like a (metaphorical, natch) knife thrust to the reader’s gut, provoking surprise, concern, even alarm. So the job of any opening chapter is to hook the reader, make her want to keep reading.In the opening pages of the chapter entitled ‘Winter,’ there’s been a murder…of a baby. That’s a hook-and-a-half right there. So from that point on each sentence, each paragraph, must give crucial clues, evidence for the thrill ride that’s in store. You can’t waste even one sentence in those crucial first few pages.

And so for me those moments spent exploring the narrator’s emotional geography are wasted moments in these all-important opening pages.

Even though Nursey is only available to the reader via telephone, it is her response that is more present for the reader. The narrator, at least in the opening, is passive, unresponsive, vacillating; and since you frame the opening chapter through the narrator’s emotional window, the opening itself feels vacillating and passive. For the reader it is Nursey’s more emotional response (she’s blubbering like a baby, after all) that provides more of a framework upon which to hang the narrative.

So by all means give us some of the narrator’s interior life at the beginning and end of the chapter. At the beginning she’s about to take her dog for a walk; it’s a relatively warm day for Western Washington, and she’s still on a high from an almost-date with the English professor. And at the end the narrator shares some of juicy details of her almost-date with coworkers. But in between these two instances, she might notice only her physical surroundings: the paint on the bumper of her Jeep is peeling, there’s a loose thread on her jacket, etc.

Of course it is important that the narrator not seem emotionally stunted or distant, this is merely a symptom of the emotional firewall she has put up to protect herself from her crazy, disjointed family — an act of personal survival, not of indifference or callousness. So on this count, by all means give us a little more of the family’s tangled history: more details about the violence-prone boys in her family, or the unstable nature of her sister Stephanie. A simple sentence or two here or there concerning past indiscretions, jail time, myriad offenses to nature or society should be sufficient.

Every other moment in the chapter spent on the narrator’s interior responses to the bad news that her nephew has been accused of murder feels to me like it pulls the reader out of the story. Better to give us Nursey’s more immediate emotional response to a tragedy that has befallen a family which seems to have had it’s fair share of tragedy.

Also, I would like to know where her nephew Anthony is, geographically, in relation to the narrator. Where does he live? What does he do for a living? Or is he unemployed? Does he always seem to be unemployed? Does he have a record or an established history of violence?

The reader wants more facts from those first few opening pages, and less privileged glimpses into the narrator’s internal workings. That can come later, perhaps in the second chapter, when the full force of what has happened to her family lands squarely on the narrator’s head.

And finally, for a chapter entitled ‘Winter,’ there seems to be remarkably little of it. You need more winter in ‘Winter.’ The dying of the leaves, the inevitable passing of time, or the (understandable) chill settling into the narrator’s heart.

Good job,

Wes

Note: Our leader of the pack David is gone fishing. We welcome and thank guest reviewer Charlie Jensen, an English teacher and published writer in Western Washington. Charlie has previously critiqued the entire manuscript, and his comments are transcribed from our last discussion of this opening section.

I’ve read this story a few times and we’ve talked about it a lot. The opening . . . is too sparse and misses some opportunities. I would like to see this section get bigger, have more feeling and catch our imagination a lot more. It is a memoir and I do accept that events are events, but that never means we can’t take poetic license.

I would like to see more scene and setting in this section. This is what you do best anyway. For example, what is happening around you while you are getting the call from Nursey—and not just about your dog. There is an opportunity to tie the surroundings into what you had to be feeling. We live in what could be the most depressing place in the world. As much as I love Washington, it is still wet, cold, gets dark at four in the afternoon and causes a lot of destruction to buildings and automobiles. It would be good to tie your feelings into that setting. Isn’t there much more to this story than, “I don’t know how to feel?” Use the setting of Bellingham to help convey the sadness this narrator already carries going into the scene. The narrator is too hidden in the opening, which needs to convey to the reader the place of detachment the narrator flees to when she gets this news. Also, where is the narrator’s mind during the discussion of the doctor?

I have told you often that what carries this story is your narrative. The e-mails [included later] alone would not make a story, and while you could make a story out of both/either Nursey or Anthony, the juxtaposition between the two stories is what gives it life—and there can only be that juxtaposition if you are firmly planted in the middle. There are four personalities in this story. There is Nursey, Anthony, your family, and you. Nursey and her illnesses, Anthony [charged with] killing a child . . . . you are the one hope, the one chance that the reader has of feeling like we can overcome all of these negatives. Just as you do for your family, you need to give your readers hope as well. That ray of hope has to be seeded at the front of the story. . . . Charlie

Well, Laurel. It’s time to tear out our hearts. This is a tragic story, and one that, as a parent, I have to distance myself from to read without sobbing. It is interesting that you originally wrote this story, thinking it was about Anthony. In the opening’s most recent incarnation, it is about how this tragedy affects you, the author, the stuff from which memoirs are made. In this prologue, you have chosen to write in present tense, but this option creates some problems for you. You are speaking to the reader in present tense, but are inserting quite a bit of interior processing that could really only happen in retrospect. I think you need to make a choice: present this opening scene in present tense and hook the reader with the enormity of the tragedy and the unusual narrative response and then write the remainder in past tense, a choice that allows you to process all that follows. OR you need to write in past tense right from the opening. This lets all the processing leak through, starting at page one. Personally, I would choose to write a prologue in present tense and the remainder in past tense.

Well, Laurel. It’s time to tear out our hearts. This is a tragic story, and one that, as a parent, I have to distance myself from to read without sobbing. It is interesting that you originally wrote this story, thinking it was about Anthony. In the opening’s most recent incarnation, it is about how this tragedy affects you, the author, the stuff from which memoirs are made. In this prologue, you have chosen to write in present tense, but this option creates some problems for you. You are speaking to the reader in present tense, but are inserting quite a bit of interior processing that could really only happen in retrospect. I think you need to make a choice: present this opening scene in present tense and hook the reader with the enormity of the tragedy and the unusual narrative response and then write the remainder in past tense, a choice that allows you to process all that follows. OR you need to write in past tense right from the opening. This lets all the processing leak through, starting at page one. Personally, I would choose to write a prologue in present tense and the remainder in past tense.

There are some lines that pull me out of the narrative, things like “pummeled by details” or “hot tears jumping to one’s eyes” that either feel cliched or not in sync with the action being presented. Other lines are beautiful: “falling to one’s knees on the cold concrete of the driveway” and “We seem to be talking in slow motion, taking a long time to speak short lines.” And still others hint at a long life filled with the pain that only family members can inflict upon one another: “The heat is generated by a falling out between my brain [I would take advantage of musical alliteration and switch to ‘head’] and my heart. They’re fighting over whether subtracting one more from the short list of family members I allow myself to love will matter in the long run.”

There are a few other places where I would eliminate some explication that can be introduced later in the story. But I think the main decision you need to make is this: revising the entire story to be about your response to this tragedy, a story that had originally been focused on the event and Anthony—and the associated temporal switch. Once you’ve done that, I think everything will fall into place. In the process, you must be fiercely attentive to the emotional truth, something that is extremely difficult to do. Good luck! Jilanne

Reblogged this on Great blogs.

Thanks for passing along our blog, Chrisknox!

Reblogged this on Great blogs.

Pingback: Group Writing Critique: BABY KILLER by Laurel Leigh | Dear Writers